Latest update: March 23, 2006

The Learning Development Institute (LDI) was a participant in the 2006 Stockholm Challenge in the category 'education.' This page was developed to present LDI's case, i.e. the story of LDI, in that particular context. We were told, though, that the story was also interesting in its own right. We have therefore decided to retain it on the learndev.org Web site.

The Stockholm Challenge searches for the best initiatives that accelerate the use of information technology for the social and economic benefit of citizens and communities around the world. LDI has an interesting story to tell regarding how to meet the challenge. That story is told on this page. Sharing our experience, which may inspire others, is our aim in telling the story.

PRIOR

CONSIDERATION: This story

parallels the description of the Learning Development Institute

(LDI) as presented in the database of the Stockholm

Challenge, which is naturally conditioned by the parameters

of that database. Considering the specific nature of LDI, the

information provided via the present description expands beyond

the elements specified in the above database, correcting, where

necessary, misconceptions that could possibly arise as well as

providing an overview that may benefit readers outside the environment

of the Stockholm Challenge. It should, for instance, be noted

that the Challenge's database situates LDI in Eyragues, France.

However, this is but one of multiple addresses across the globe

with which LDI can be associated. At the heart of LDI's existence

is the notion of networking. As explained below, this means that

LDI is not based, but distributed, a characteristic it owes,

in large part, to how it has taken advantage of the Internet.

It also seems appropriate to state candidly that, while LDI engages

in developing innovative uses of technology, its goals are beyond

the technology as such and the area it covers is much broader

than technology-based interventions. In what follows, the focus

is therefore on the purposes for which LDI was created, rather

than its significant role in developing and promoting the pioneering

human use of technology.

PRIOR

CONSIDERATION: This story

parallels the description of the Learning Development Institute

(LDI) as presented in the database of the Stockholm

Challenge, which is naturally conditioned by the parameters

of that database. Considering the specific nature of LDI, the

information provided via the present description expands beyond

the elements specified in the above database, correcting, where

necessary, misconceptions that could possibly arise as well as

providing an overview that may benefit readers outside the environment

of the Stockholm Challenge. It should, for instance, be noted

that the Challenge's database situates LDI in Eyragues, France.

However, this is but one of multiple addresses across the globe

with which LDI can be associated. At the heart of LDI's existence

is the notion of networking. As explained below, this means that

LDI is not based, but distributed, a characteristic it owes,

in large part, to how it has taken advantage of the Internet.

It also seems appropriate to state candidly that, while LDI engages

in developing innovative uses of technology, its goals are beyond

the technology as such and the area it covers is much broader

than technology-based interventions. In what follows, the focus

is therefore on the purposes for which LDI was created, rather

than its significant role in developing and promoting the pioneering

human use of technology.

NOT YOUR USUAL INSTITUTE

The

Learning Development Institute (LDI) operates decidedly outside

the mainstream and it shows. It doesn't fit the regular criteria

used to describe projects, whether for the Stockholm Challenge

or otherwise. LDI's focus is on human learning, and human learning

interacts with all six areas according to which entries for the

Stockholm Challenge are classified, i.e. Public Administration;

Culture; Health; Education; Economic Development; and Environment.

We have chosen, however, to list LDI under the category Education.

Education comes closest to the conscious concern with learning,

even though in the practice of education that same concern often

remains limited to what happens in the school and little attention

is given to the myriad other ways and settings in which people

learn. LDI interprets learning in a much broader sense than what

is reflected in the usual concern with education. It looks at

the phenomenon of learning in the perspective of what human beings

do that dispositions them to interact constructively with change.

The adverb 'constructively' is important here. It gives a moral

dimension to learning. Many articles in the 'papers' section

on LDI's Web site elucidate the Institute's views on learning.

A definitional source is Jan Visser's (2001) chapter on Integrity, Completeness and Comprehensiveness

of the Learning Environment: Meeting the Basic Learning Needs

of All Throughout Life in the International Handbook

of Lifelong Learning. The link provided gives access to an unedited

version of that chapter.

LDI is clearly mission oriented. The mission that guides LDI's work is comprehensive.

Its 'target audience' is humanity at large and the geographical

area where it seeks to have an impact is as vast as the surface

of a small planet, called the earth. As a consequence, LDI could

never be effective if it defined itself in traditional institutional

terms. By necessity, its focus has to be on networking, symbiosis

and catalysis. It has existed now for more than five years and

has not only survived, but flourished. To do so, it has never

had to ask anyone to contribute financially to the sustainability

of the institution. How that was possible will be explained more

fully in one of the following sections. Here we merely want to

reiterate a point made in LDI's 2005

Annual Report, which asserts that "LDI has stayed keenly

attuned to emerging technological developments and has been an

early adopter [Rogers, 1995] of them, particularly as regards

the broad variety of IP-based technologies. It is no exaggeration

to state that it would have been impossible for LDI to become

what it presently is had it not been possible to take advantage

of these technological developments. Besides the opportunities

such technologies afforded for effective communication, it is

at least as important that they were available at an extremely

low cost" (10).

NOT A PROJECT EITHER

LDI is more than a project. Rather, it is a challenge; one that requires long-term strategic thinking beyond the timeframes of regular projects. LDI emerged from earlier work undertaken in the context of UNESCO's Learning Without Frontiers (LWF) initiative. LWF was initially started as an effort to break down the traditional barriers to learning, related to space, time, age, and circumstance. But it soon became clear that in addition to those barriers, there are many other - often more fundamental - barriers in the ways in which we perceive of learning. Those perceptual barriers impact the kinds of learning societies try to facilitate and the many other aspects of learning that never get attention. LDI, which is the successor to LWF, represents the challenge to tackle the latter kind of barriers, or, as we once formulated it, to work towards Overcoming the Underdevelopment of Learning. The link provided in the previous sentence leads to the papers that emerged from holding a symposium in 1999 in the context of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, held in April of that year in Montreal, Canada. Organized collaboratively by LDI and UNESCO, that symposium can be seen as a first instance of the building of transdisciplinary networked learning communities around issues of significance that has since become the mainstay of LDI's work.

LOOK, NO WALLS!

The

focus on building of transdisciplinary networked learning communities

to address fundamental issues in the development (or lack thereof)

of human learning has been responsible for another unique characteristic

of LDI: the Institute has no walls. The question 'Where

are you based?' cannot be answered in the case of LDI. We

are not particularly proud of it. In fact, those who identified

with LDI in its early years rather experienced a kind of embarrassment

when they were not able to answer such a simple question. After

all, if you are not based, do you really exist? It is a feature

of having one's focus on networking that 'presence' becomes something

increasingly less defined. One becomes present through others,

rather than in one's own right, through a symbiotic relationship

with persons and organizations. Such presence is not automatic.

It is not a simple function of the number of links one establishes,

but rather of the quality of such links. And that quality, in

turn, is related to the work one does together with others. Thus,

virtual presence is a distributed 'being there' in the creative

collaboration with other people and institutions.

The

focus on building of transdisciplinary networked learning communities

to address fundamental issues in the development (or lack thereof)

of human learning has been responsible for another unique characteristic

of LDI: the Institute has no walls. The question 'Where

are you based?' cannot be answered in the case of LDI. We

are not particularly proud of it. In fact, those who identified

with LDI in its early years rather experienced a kind of embarrassment

when they were not able to answer such a simple question. After

all, if you are not based, do you really exist? It is a feature

of having one's focus on networking that 'presence' becomes something

increasingly less defined. One becomes present through others,

rather than in one's own right, through a symbiotic relationship

with persons and organizations. Such presence is not automatic.

It is not a simple function of the number of links one establishes,

but rather of the quality of such links. And that quality, in

turn, is related to the work one does together with others. Thus,

virtual presence is a distributed 'being there' in the creative

collaboration with other people and institutions.

SYMBIOSIS AND CATALYSIS

Two ideas are central to how LDI exists: symbiosis and catalysis. Symbiosis can be described as “an association between different organisms that leads to a reciprocal enhancement of their ability to survive” (e.g. Lee, Severin, Yokobayashi, & Ghadiri, 1997). Catalysis is the process of lowering the required activation energy for a (bio)chemical reaction, leaving the catalyst itself unchanged. A catalyst can thus speed up a specific process. Catalysis can bring about change in situations that are otherwise entirely stable, leaving the catalyst intact to continue to perform a similar role elsewhere (e.g. Watson, Hopkins, Roberts, Steitz, & Weiner, 1987).

The idea of symbiosis at an organizational level means that, as an institution, one does not exist merely for oneself, but always together with and for others, whose existence is being enhanced by one's own existence and vice versa. Similarly, and as a consequence of being symbiotic, it is natural also to care for one's environment without being or becoming part of desired change processes oneself or having a direct interest in them. In terms of networking this means that one cares for network relationships even if one is not oneself in the center of things, i.e. one behaves like a catalyst. LDI operates at both levels.

THE ROLE OF THE INTERNET AND TECHNOLOGY APPLICATIONS

As mentioned, LDI would not have been what it is without the Internet. The existence of the Internet has been a necessary condition for the development of LDI. However, it has not been, and will not be, a sufficient condition.

Hubert

Dreyfus (2001) argues that living on the Web, leaving our bodies

behind, leads to eliminating risk, vulnerability and commitment.

Summing up a New York Times article by Guernsey (2000)

he asserts that "embodied people with their sense of relevance

cannot be dispensed with but need to form a symbiotic relation

with the disembodied machines" (96), lest meaning will disappear.

Meaning is at the heart of LDI's work. In fact, the very first

focus area of activity the Institute identified, and the one

that has seen the most far reaching development and that interacts

most universally with all subsequently defined focus areas is

called the Meaning of Learning (MOL).

While LDI could never have become in a mere five-year time span

what it currently is without the Internet and other ICTs, it

would also never have become what it is if it had not at the

same time cared for the embodiment of thought in real-life experience,

creating opportunities for bodily togetherness and emotional

involvement among thinkers, researchers, practitioners, activists

and decision makers, asking participants in LDI's spaces of dialogue

to bring their bodies as much as committing their minds and souls.

Thus, physical systems of transportation of human bodies are

seen as inseparable from electronic links in LDI's work to network

the best and most committed minds of the planet.

Hubert

Dreyfus (2001) argues that living on the Web, leaving our bodies

behind, leads to eliminating risk, vulnerability and commitment.

Summing up a New York Times article by Guernsey (2000)

he asserts that "embodied people with their sense of relevance

cannot be dispensed with but need to form a symbiotic relation

with the disembodied machines" (96), lest meaning will disappear.

Meaning is at the heart of LDI's work. In fact, the very first

focus area of activity the Institute identified, and the one

that has seen the most far reaching development and that interacts

most universally with all subsequently defined focus areas is

called the Meaning of Learning (MOL).

While LDI could never have become in a mere five-year time span

what it currently is without the Internet and other ICTs, it

would also never have become what it is if it had not at the

same time cared for the embodiment of thought in real-life experience,

creating opportunities for bodily togetherness and emotional

involvement among thinkers, researchers, practitioners, activists

and decision makers, asking participants in LDI's spaces of dialogue

to bring their bodies as much as committing their minds and souls.

Thus, physical systems of transportation of human bodies are

seen as inseparable from electronic links in LDI's work to network

the best and most committed minds of the planet.

Not the technology, but commitment to a valid cause is the key driver of LDI's success. Technology, and particularly the Internet, has been the prime facilitating factor to serve the cause. Or, as Dreyfus (2001) asserts: "If...one is already committed to a cause, the World Wide Web can increase one's power to act, both by providing relevant information, and by putting committed people in touch with each other who share their cause and who are ready to risk their time and money, and perhaps even their lives, in pursuing their shared end" (103).

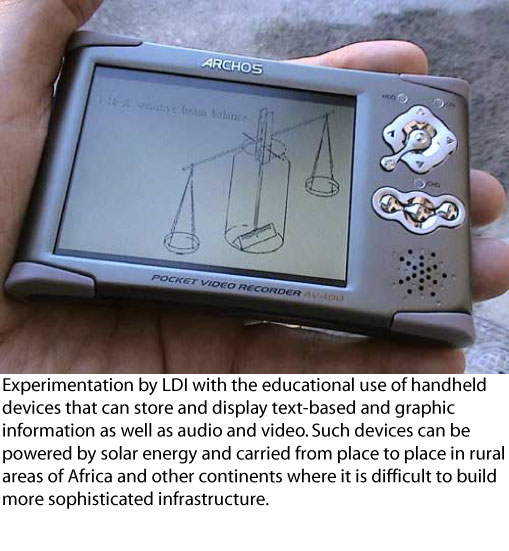

Thus, the key innovative aspect of the use of ICT to implement LDI's mission is that it is not taken for granted that the technology will do the trick. Every application is carefully thought through in terms of the interaction between the human beings involved while using the technology. Careful attention is given to what needs to supplement ICT-enabled processes or how ICTs might enhance courses of action that are not in the first place technology-enabled. This applies both to how scholarly networks are being facilitated (often with the inclusion of relevant opportunities for face-to-face contact among participants) and to how LDI promotes the integration of technology at the field level of application. For instance, thanks to LDI's intervention, major recommendations were made to reorient a development project in the Democratic Republic of Congo away from a too strong emphasis on technology via community telecenters to giving primary attention to learning and teaching, integrating the use of ICT from the perspective of how it would best serve specific pedagogical purposes. The use of technology by LDI is always explored from the perspective that it should enable users to be optimally creative in solving problems autonomously and collaboratively.

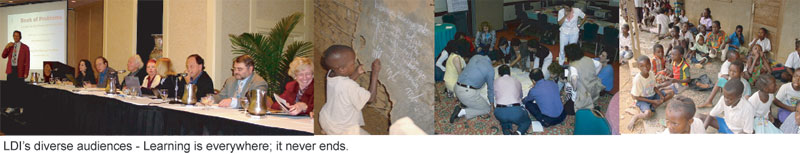

LDI'S AUDIENCES

Learning has no end. It affects everyone, independently of age, gender, or whatever other distinctions can be made to separate people in specific groups. However people are divided up, LDI's work is relevant for all of them. There are no specific target groups. Thus, those who become involved in and who are affected by LDI's work range from the newly born to the dying; from poor to rich; they include the sick and healthy; and they may equally well live in the most remote rural areas as well as in sophisticated urban environments. They may or may not have access to information and communication technologies.

In practice, the above has meant that LDI has worked extensively at the frontier of the development of knowledge and insight into how humans learn through interaction with the most advanced intellectual communities as well as helped improve the conditions of learning for children and adults in remote disease infected impoverished rural areas in Central Africa where schools - if they exist - are far in between, where there is no electricity, telephone or Internet, and where radio signals may not penetrate with sufficient clarity and loudness to serve a useful purpose.

IMPACT

Changing mindsets, which is what LDI is in the first place about, may take more than one generation. It cannot be measured in terms of a headcount of converted individuals. Rather, the success can be gleaned from indicators that show that serious and profound thinking is going on. Below is a list of select indicators that, in our view, reflect LDI's impact.

- Success in inviting the best minds on the planet to contribute to LDI's intellectual effort. Level of accomplishment and recognized stature of the individuals who contributed to the work of the variety of communities generated by LDI is testimony to the impact represented by this indicator. Exemples are the Building the Scientific Mind Community, the Book of Problems community and the 9/11 community.

Perceived

importance attributed to LDI's Web site as measured by the Google

page rank, which has for several years remained 6/10. This is

comparatively impressive as argued in the 2005

Annual Report of the President of LDI. It is particularly

impressive considering that LDI has 0 (zero) staff on its payroll.

Perceived

importance attributed to LDI's Web site as measured by the Google

page rank, which has for several years remained 6/10. This is

comparatively impressive as argued in the 2005

Annual Report of the President of LDI. It is particularly

impressive considering that LDI has 0 (zero) staff on its payroll.

- Acceptance of submitted papers and proposals for conference sessions in peer reviewed environments. We have had not a single reject over the entire five year period.

- Quality and formal recognition of the channels through which LDI's work gets known. Example: A major chapter redefining the concept 'learning' in the sense envisioned by LDI got published in 2001 in the authoritative International Handbook of Lifelong Learning published by a top-notch publishing house, Kluwer Academic Publishers. A similar argument applies to the scientific and professional journals in which LDI publishes and the scientific conferences to which it contributes.

- Frequency of invitations to deliver keynotes, to conduct workshops, and to participate in projects, etc. Almost from the start of LDI's work, requests have outnumbered the capacity to respond.

- The extent to which initiatives are being emulated by others. A case in point are the Building the Scientific Mind workshops currently being organized in India and Russia by participants in the recently held Building the Scientific Mind colloquium.

Successful

implementation of projects. Through the provision of needs assessment

and advisory services, LDI played for instance a major role in

shaping the earlier mentioned development

project in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Thanks to its

part in the success of this project, LDI is now being asked by

two competing consortia to join them for a follow-on project.

120 primary schools in rural areas benefited from the project

in terms of improved access (including via Internet); improved

pedagogy; improved gender ratio (more girls); improved capacity

to use local resources to support the pedagogy; and improved

relevance of what is being learned.

Successful

implementation of projects. Through the provision of needs assessment

and advisory services, LDI played for instance a major role in

shaping the earlier mentioned development

project in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Thanks to its

part in the success of this project, LDI is now being asked by

two competing consortia to join them for a follow-on project.

120 primary schools in rural areas benefited from the project

in terms of improved access (including via Internet); improved

pedagogy; improved gender ratio (more girls); improved capacity

to use local resources to support the pedagogy; and improved

relevance of what is being learned.

- Success in generating freely available resources for autonomous learning. A shining example of this is the collaborative project For the Love of Science, executed in collaboration with renowned scientists (Roy McWeeny being editor in chief) and the Pari Center for New Learning. Academics at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) in South Africa have recently joined the partnership. Collaboration with the UWC will focus on improving and validating the materials. Readers will appreciate the exceptional nature of this project by exploring the materials currently available.

- The effective spawning of initiatives that are entirely new and that no one else in the world is working on. An example is the development of work around the idea that attention to mindsets needs to complement the traditional emphasis on competencies in the design and planning of learning opportunities. Initial emphasis in this regard is on the scientific mind, which recently led to the Advanced International Colloquium on Building the Scientific Mind. A particularly interesting offshoot of the latter initiative is the creation on an international research and development network regarding the connection between HIV/AIDS related behavior and the scientific mind. Work of the latter group will have essential implications for strategies to combat HIV/AIDS in the developing world and elsewhere.

- Other indicators of impact are the spontaneous positive feedback received from users of the ww.learndev.org Web site; reported use of material available on the Web site at universities and research institutions; and spontaneously received requests from relevant scholars to join specific efforts.

ECONOMIC MODEL, SUSTAINABILITY AND REPLICABILITY

The economic model according to which LDI is organized and was allowed to develop is believed to be unique. Unlike non-governmental organizations in general, LDI has never sought or received funding to sustain its own existence. It generates income – annually some $ 15,000 on an average – by providing services. It has been able to do everything it does at an average yearly budget of less than $ 10,000. In other words, LDI operates at virtually no cost (no pun intended) to the outside world. Its cost effectiveness is thus extremely favorable. The fact that no one’s living depends on LDI allows the organization to pursue sustaining itself in an entirely non-competitive manner, focusing on the declared purposes for which it was created. The model has been in place for five years. It is perfectly sustainable and believed to be replicable by others, provided a number of conditions are satisfied. LDI's 2005 Annual Report analyzes those conditions as follows:

A prime condition of sustainability for the model of functioning chosen by LDI is the intrinsic motivation and dedication to a cause by those who drive the organization in addition to the availability to such individuals of sufficient alternative means to sustain themselves. Such alternative means can for instance be derived from a regular job in a different context with time left to dedicate oneself to other important issues; independent retirement benefits or other forms of independent wealth; or an already financially assured setting in which someone undertakes a study and, as part of that effort, seeks an opportunity to enhance the study environment by linking it to a relevant sphere of intellectual pursuit in line with the objectives of the study. LDI has benefited from all such opportunities. Typically, those who contribute to its work voluntarily range from students to highly accomplished retired professionals. The question is not if such potentially available work input exists. It is there, and in some cases abundantly so. The more important question relates to how it can be mobilized for a desired purpose. People who are free to choose will dedicate their voluntary effort to options of their choice, selecting one opportunity over the other.

Several factors are believed to have worked in favor of LDI's model of sustainable mobilization of voluntary efforts.

- LDI has actively positioned itself in relevant professional circles, providing it with visibility and credibility.

- LDI has actively published its results and publicized its efforts via alternative media, such as books, journals, the printed press in general, radio, TV, and multiple Internet-based fora, including its own Web site. While doing so, it has selectively chosen the channels through which it communicated, keeping in mind the size of the audience reached and the perceived relevance and reliability of a particular channel.

- LDI has actively responded to requests for keynotes, invited papers, workshops and the like in contexts that could be expected to enhance its visibility and to contribute to its perceived relevance by association with others, perceived to be relevant by LDI.

- LDI has created a small network of select Fellows and other associates of outstanding achievement in fields relevant to LDI's work among individuals whose ages and levels of accomplishment vary widely. Their presence often serves as an attractor to others who seek to join.

- LDI has stayed keenly attuned to emerging

technological developments and has been an early adopter of them,

particularly as regards the broad variety of IP-based technologies.

It is no exaggeration to state that it would have been impossible

for LDI to become what it presently is had it not been possible

to take advantage of these technological developments. Besides

the opportunities such technologies afforded for effective communication,

it is at least as important that they were available at an extremely

low cost.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Symbiosis and catalysis have been the mainstay of LDI’s

work since the organization started its activities. It sets LDI

– and a small number of like-minded organizations –

apart from the large majority of organizational entities (whether

for profit or not for profit), who, independently of what their

mission statement may specify, also represent the understandable

interest of those who work in and for them to have a stable job.

No one’s livelihood depends in an immediate sense on LDI’s

continued existence. The organization can thus be genuine in

its declaration that it exists for a purpose and has no intention

to survive that purpose. However, all indications are that LDI's

objectives are still far from being fulfilled. Thus, the Institute

must continue to pursue its aims.

Technology will continue to play the crucial role it has played so far. No salary costs being involved, the benefits from even small investments in technology will be relatively high. However, we trust our experience that technology, even when crucial, should not be the key focus of attention in addressing the need to develop human learning. Learning is a social and dialogic process. It takes place between people. However powerful the technological means, they can only be effective if their use is appropriately designed to facilitate in an optimal fashion embodied human-human interaction.

LDI is determined to retain and consolidate its current position as a symbiotic and catalytic entity. Preserving those key elements of LDI’s existence is essential to its mission. It is also essential to retaining the level of autonomy that has allowed LDI to address the non-mainstream issues to which it dedicates itself. It is what has allowed LDI to retain its excellence in the sense of going beyond where others are. The financial implications of this position are obvious. It would be counter to LDI’s mission if the organization were forced to attribute priority to issues of its own institutional survival in terms of fulfilling financial needs. The five-year history of LDI provides sufficient evidence to support the conclusion that it can sustain its growth at the pace at which it has so far developed. This provides LDI with a convenient level of comfort to experiment with supplementary modes of functioning while maintaining its current level of autonomy.

This opportunity comes at a good time The thematic focus areas have developed – thanks also to the ongoing dialogue that LDI has stimulated and facilitated over the years – to the extent that research questions and development options start emerging that call to be addressed. Considering the transdisciplinary nature of most of these research questions and development options it is unlikely that more traditional organizations will take them on. Thus, LDI starts finding itself in a position that it is morally obliged to follow through on the results of its work and, in addition to being catalytic, also take on well-proportioned active leadership positions in carefully selected areas. Over the next five years the Institute intends to develop its capacity to play such an enhanced leadership role.

REFERENCES

Dreyfus, H. L. (2001). On the Internet. London and New York: Routledge.

Guernsey, L. (2000). The search engine as Cyborg. The New York Times, June 29, 2000.

Lee, D. H., Severin, K., Yokobayashi, Y., & Ghadiri, M. R. (1997). Emergence of symbiosis in peptide self-replication through a hypercyclic network. Nature, 390, 591-594.

Rogers, E.M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th edition). New York: The Free Press.

Visser, J. (2001). Integrity, completeness and comprehensiveness of the learning environment: Meeting the basic learning needs of all throughout life . In D. N. Aspin, J. D. Chapman, M. J. Hatton and Y. Sawano (Eds.), International Handbook of Lifelong Learning (Vol. 2, pp. 447-472). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Visser, J. (2005). President's annual report to the board of directors for its meeting of July 20, 2005. Eyragues, France: Learning Development Institute [Online]. Available: http://www.learndev.org/dl/AnnualRpt2005.pdf [2005, July 24].

Watson, J. D., Hopkins, N. H., Roberts,

J. W., Steitz, J. A., & Weiner, A. M. (1987). Molecular

biology of the gene. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings Publishing

Company, Inc.